How to Be a Self-Taught Illustrator

10 tips for the self-taught children's book illustrator — Roy P. Awbery

One doesn’t need to train to be a book illustrator to create and publish one’s own children’s storybooks. Almost anyone can do it - with a bit of practice and commitment. I’m an entirely self-taught artist who decided to write and illustrate my own children’s books, the first of which “The Scariest Dinosaur” has done really well on Amazon. Here are my top ten tips for illustrating your own storybook.

1. Practice. Practice. Practice.

It’s stating the obvious but if you want to become successful or proficient at anything you need to practice and practice a lot. When I decided that I wanted to create a storybook for my grandchildren I found that, despite being a successful artist, I was pretty much hopeless at illustrating. My first attempts were not great. But, I persevered and did a lot of research, and kept at it. It didn’t take long before I began to understand how illustrations were put together.

I highly recommend reading and reviewing as many children’s books as you can. There are so many out there and they are all of varying quality but you will soon see that there are relatively few styles that they can be categorised into. Once I found this I was able to decide which style I wanted to develop for myself.

Of course, you might think your illustrations are great so it is also a good idea to get some outside reviews and this is where my 2nd tip comes in.

2. Seek Advice and Opinions

This might sound scary but I found that setting up an Instagram account and dedicated Facebook page for my artwork was invaluable in terms of getting feedback. As I was developing my style I would post my works in progress and ask people to let me know what they thought. You have to be a little thick-skinned for this as some people can be rather brutal. However, most people do offer constructive criticism and suggestions - people know what they like and dislike.

I also sought the opinion of primary school teachers and children. This makes perfect sense - I will eventually want to sell this book to this audience so understanding what they want and like is essential.

3. Develop your own style and stick to it.

Many children’s authors do not create their own illustrations and if you look at some of the top illustrators you will see that there is consistency in their work, regardless of who they are illustrating for. A great example of this Axel Scheffler whose work can be seen in many of Julia Donaldson’s storybooks.

Once you find a style you look keep practicing with your sketches until you see your own style come through - and it will. The aim here is not to simply copy another artist’s work but to use them to help you learn how to illustrate and find what you are most comfortable with.

4. Understand what an illustration is.

This is important! When I started out I really didn’t understand what defined an illustration and made it different from a simple picture. Put simply, and rather obviously, an illustration illustrates! It is intended to add to the story and convey more information to help the reader and add more information and context.

Many illustrated children’s books follow a simple 32-page format with around 500 words. This really is not a lot and so one has to be economical with word use and this is where illustrations become invaluable. For example, if a scene in your story is set in a farmer’s field on a sunny day with a scarecrow nearby and lots of crows swirling overhead then there is no need to say this in words - it can all be shown in the illustration. Similarly, if a character has departed and left behind a scene of chaos and mess there is no need to say it because the reader will be able to see it.

Another aspect of illustrating for children is that I found they love to find things that are not mentioned in the story. I began placing random creatures such as mice and rabbits in my illustrations and found that children loved them. They get great delight from spotting something partially hidden or seeing other characters playfully interacting in the scene.

5. Decide on a colour palette.

Every artist is self-taught, in a way

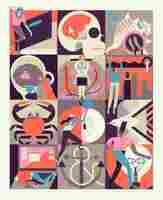

Owen Davey is an award-winning illustrator living in Leicestershire, UK.

Owen’s portfolio is nothing short of impressive – and you may already be familiar with his work, as his illustrations have been published “in every continent except Antarctica”, as he himself mentions. His work ranges from children’s books to magazines, branding and mobile game apps. His clients include brands like Orange, Microsoft, Persil, The New York Times, BBC and Jamie Oliver.

His style is that he uses a fairly limited color palette for each illustration, and creates geometric shapes and textures to bring the stories to life. And if, like me, you were thinking that you might need some fancy tablet and great knowledge of Adobe Illustrator to make your drawings look like this, well, think again. Owen is surprisingly low-tech and, after drawing the initial sketches on paper, he only uses a mouse and Photoshop to create his illustrations. Which, you have to admit, is pretty amazing!

Every artist is self-taught in a way, I think

You have graduated from University College Falmouth with a BA in Illustration. How has school helped your career? Do you think you could have gotten to where you are now, if you were self taught?

Falmouth was an amazing course where they spent a lot of time focusing on professional practice, things like colour theory, conceptual thinking, composition, writing books etc. I learnt a massive amount and think I’m a much better illustrator due to them. I think of myself as sort of self-taught as well though. Every artist is in a way, I think. You can feed off the ideas and technical advice from people but at the end of the day, you have to be the one to put the work in and learn by doing.

You have a style that is pretty easy to recognize, from combining geometric shapes and textures to keeping a coherent color palette across all your work. What are the factors that influence your work, what’s your inspiration?

I’m inspired by everything and I’m regularly discovering stuff which I love, which I’m sure influences my work. My ‘style’ has actually changed a lot over the years, but I love playing with colour and shapes. I’m in awe of a lot of mid-century artwork, and really enjoy the limited colour palettes and simplification techniques used by many artists throughout those times.

You are a freelance illustrator. How do you manage your time, so that you are able to meet deadlines and easily switch from one project to the next? Is there a recipe for that?

Yeah, that’s one of the toughest parts of the job. Managing my time has been a big learning curve and I don’t always get it right. I’ve never missed a deadline, but I have had to do several all-nighters and some long long stints of long work hours. I think I’m getting the balance a bit better these days but there are still times where it gets a bit manic. I’ll probably never perfect it. I just want to do everything, which can cause issues hehe.

Your portfolio includes some pretty big clients, like Facebook or Unilever. How did you first get to work with well-known brands like these?

There is a mix of ways really. I reach out to some clients, my agents reach out to some too, and some reach out to me after seeing my stuff in other publications, on my website, in books, or on social media. I do a lot of self-promoting.

Talking about having agents, how is that helping your work? Do you feel that paying a commission to the agent is worth it, is it saving you a lot of time and effort on new projects?

I absolutely love my agents. I have had a wonderful working relationship with them and they always have my back. They are definitely worth paying a commission to. I know that not all agents are like this though. I just got a pretty lucky, I think.

In your experience, is there a difference between working with big clients and small ones? Which do you enjoy more? Why?

It’s not really the size actually that makes the biggest difference. Some big ones are surprisingly awesome about giving you creative freedom. And some small ones can be infuriatingly picky. There isn’t a formula. Although I have to say that some of my favourite commissions have been for very small trade magazines. I don’t know why but they tend to offer you a lot of respect and really appreciate what you do, just handing over the reigns and steering only when necessary.

Some big clients are surprisingly awesome about giving you creative freedom. And some small ones can be infuriatingly picky

When I look through your portfolio, the Smashmallow project is one of my favorites. What was the brief there? I’m curious what the story is, what was the journey from the initial ideas until the final result we see now.

So with most packaging and advertising projects, clients tend to be understandably quite prescriptive. Smashmallow were actually quite relaxed compared to most, but they came to me with the rough idea of worlds based on the flavours of the marshmallows. From that we then had a lot of back and forth over the best routes to take and what to feature, with several rounds of feedback. I’m really happy with the results though. It was a great collaborative effort.

You have several books published, tell me a little about that. How did you first get the idea of publishing a book? And how did you come up with the subject?

My answer to the kid question of “What do you want to do when you grow up?” was always “I want to write and draw the pictures for children’s books”, so it was something I pushed toward for years. And I love doing them. They take up a lot of time though, so I’m limiting how many I do in a year now. My first published book was “Foxly’s Feast” and I actually wrote it and illustrated a lot of the book at the beginning of my third year at Falmouth University. The lovely man (Mike Jolley) then saw the potential in it and helped me get it through his publishers, Templar. Each of the ideas for the books are usually spawned from little thoughts I have whilst living my life, which I note down in a sketchbook and discover at a later date, expanding it into several pages. Although my non-fiction books are much more labour-intensive than that, and are born out of an excessive amount of research.

I’m inspired by everything and I’m regularly discovering stuff which I love, which I’m sure influences my work.

Is it working out so far, are people buying your books?